Undressing to create

- Claude Gauthier

- 5 days ago

- 13 min read

Vulnerability, truth, and presence

Undressing in front of a photographer places the model in a state of vulnerability. This stripping away, both physical and psychological, opens a space where masks literally fall away. In this suspended moment, the model is no longer armored: they present themselves in their raw state, as they are, without decorum, without pretense. This fragility is not a weakness, but a direct path to authenticity.

It is in this state of accepted vulnerability that the strongest connections to truth are revealed. Authenticity is born when the usual defenses of daily life disappear: social postures, roles, expectations. What the camera then captures is not a fabricated image but a moment of raw sincerity. Nudity becomes a language, a way of saying, "This is who I am, even before what I show."

In this space of trust, emotions can be expressed in their full range:

calm neutrality , close to meditation or inner rest;

amusement , when the situation brings about unexpected spontaneity;

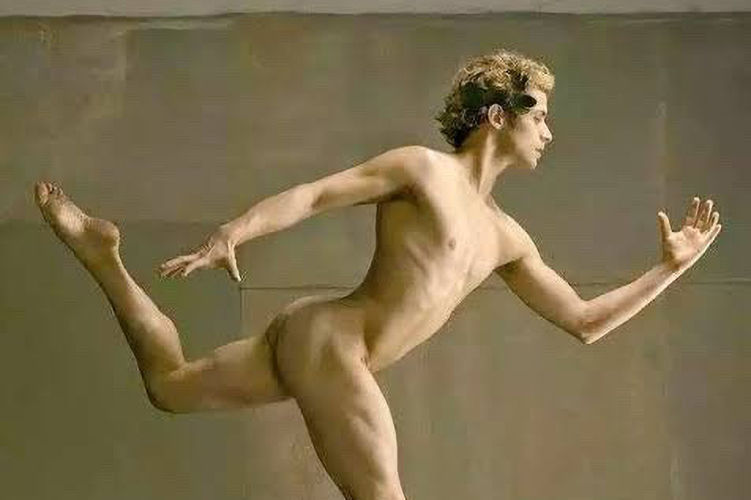

state of extreme alertness , when the body suddenly feels hyper-present in the world;

introspection , when the model turns towards what is happening within him rather than towards the objective;

anger or tension , when something buried rises to the surface

heroic presence , when the body straightens up as if to affirm its existence.

All these nuances constitute an emotional grammar of truth, an expressive range that escapes play and approaches human truth.

Michelangelo's David: A Legacy of Heroic Vulnerability

The reference to Michelangelo's David sheds light on this approach. Although David is depicted before the battle, in a pose of controlled power, he is nonetheless naked, exposed, unprotected, laid bare for all to see. This nudity is not erotic: it is a symbol of truth, courage, and humanity. Michelangelo shows a hero not in his victory, but in his moment of doubt and conscious vulnerability, where inner tension is at its peak.

This parallel is invaluable for contemporary photography. The model, like David, is not performing but embodying a presence, where the body expresses a profound emotion. The photographer, then, does not capture a naked body: he seizes a human being at the precise moment of their self-revelation.

Towards an aesthetics of sincerity

In this dynamic, undressing becomes an artistic act in itself, a stripping away of artifice to reach a state of emotional transparency, where truth is no longer an abstract idea but a face, a gesture, a breath. The photographer, a silent witness, welcomes this vulnerability and transforms it into an image. Authenticity cannot be forced; it emerges when trust is absolute.

Thus, nudity in photographic art is not so much an exhibition of the body as an exhibition of truth. And it is from this encounter, fragile yet powerful, that the work is born.

Creative vulnerability vs. exhibitionism: two opposing intentions

When a model undresses for art, they enter a state of vulnerability profoundly different from that of exhibitionism. Artistic nudity arises from an inner gesture, an opening of the self that implies fragility, honesty, and trust in the photographer. It is oriented towards the search for truth. The model does not seek to be admired, but to be seen in what they embody that is sincere, human, and sometimes imperfect. Nudity then becomes a subtle language, an expressive material placed at the service of an exploration of identity, emotion, or symbolism.

Exhibitionism, on the other hand, is based on an intention of active seduction, even provocation. The model who exhibits themselves consciously seeks the gaze, the impact, the stimulation that comes from being observed. They derive personal satisfaction from the self-disclosure, as if the attention of the other becomes a source of energy or validation. Here, the dominant emotion is not vulnerability, but the pleasure of being exposed. The gesture is directed outward, toward the effect produced on the observer.

In artistic vulnerability:

The viewer's gaze is welcomed but not sought;

nudity serves to reveal the inner self;

the model accepts not controlling his own image;

The gesture is one of abandonment, sometimes silent, sometimes anxious.

In exhibitionism:

The gaze of the other is central and invoked;

nudity is used to assert power, sexual identity, or domination of the body;

the model controls the scene and orchestrates perception;

The gesture is laden with intention and conquest.

One exposes the being, the other exposes the body

Where vulnerability seeks emotional truth, exhibitionism seeks effect.

Where one invites us to contemplate the human, the other invites us to consume a presence.

Where one reveals inner turmoil, the other stages an expansion of desire.

This distinction is essential in the context of a true artistic approach: nudity, when it carries vulnerability, opens the door to a psychic depth that exhibitionism, by its very nature, is not intended to reach.

Sensuality vs. sexuality: two emotional registers, two spaces of the gaze

Sensuality and sexuality, though related, belong to two radically distinct aesthetic universes, especially in the context of the artistic nude. The model who expresses sensuality enters a realm where the body becomes symbol, presence, breath. Nothing is explicitly oriented towards the sexual act: what dominates is beauty, grace, suggested desire, the enigma of the living body.

Sensuality is an art of the threshold. It opens the door to desire, but does not cross it. It leaves room for the imagination, for dreams, for the spectator's inner projection.

Sexuality, on the contrary, introduces a gesture of direct revelation: it emphasizes explicit arousal, bodily intimacy, and the private dimension of the experience. Where sensuality elevates the gaze, sexuality directs and fixes it within a narrower register: that of assumed eroticism or displayed pleasure.

Sensuality: an aesthetic emotion, not an intimate one.

The model that expresses sensuality draws on a refined emotional register, linked to:

the beauty of shapes and lines;

the gentleness of the gesture;

open but non-sexualized vulnerability;

poetic abandonment;

Human closeness, not excitement.

Sensuality is never a call, but a silent invitation to perceive. It emanates from bodily attitude, breath, gaze, the shaping of light.

This is exactly what Michelangelo's Dying Slave conveys.

Her body is naked, abandoned, traversed by a gentle tension between life and sleep. Nothing is obscene. Nothing is sexually explicit. And yet, the sculpture overflows with intense sensuality, a sensuality that comes from the curves, from the marble that seems to breathe, from the spiraling movement of the torso.

Michelangelo does not show a desiring man, but a body that projects purely human beauty, in its fragile, carnal and ephemeral aspects.

Sensuality therefore belongs to the public space of art: it can be contemplated without embarrassment, because it falls under the symbolic, the poetic, the sublime.

Sexuality: an intimate, not aesthetic, emotion

Sexuality, on the other hand, shifts towards the realm of private intimacy.

It transforms the spectator into a voyeur, because it introduces him into a space where he does not normally belong: that of sexual experience, of the act, of arousal. The body is no longer form or symbol: it becomes an object of excitability.

The looks, the poses, the gestures become oriented towards a single purpose: to arouse physical desire, sometimes direct stimulation.

In photography, this radically alters the dynamics of the gaze. The artist no longer invites contemplation, but rather entry into a private space. The observer ceases to be a witness: they become an implicit participant.

Where sensuality elevates, sexuality brings down.

Where sensuality suggests, sexuality exposes.

Where sensuality allows for poetry, sexuality imposes an interpretation.

The essential boundary for the art of the nude

For the photographer, this distinction is essential.

A model can be nude, expressive, dreamy, vulnerable, intensely alive without ever crossing into the sexual realm. What matters is the intention behind the gesture and the quality of the emotion conveyed.

Sensuality:

a space for noble emotions;

an aesthetics of perception;

an appeal to dreaming and contemplation;

a physical presence that speaks without forcing.

Sexuality:

a space for intimate emotions;

a dynamic of stimulation;

an intrusion of the gaze;

a proximity that abolishes respectful distance.

Sensuality presents the body as a poetic presence . Sexuality presents the body as an object of arousal. The former belongs to art. The latter belongs to the private sphere.

Nudity as a site of domination: the paradigm of Marsyas

In the history of art, nudity is not only linked to eroticism, beauty, sensuality or vulnerability: it can also be the terrain of absolute domination, of symbolic or ritual violence.

The myth of Marsyas, the satyr who challenged Apollo to a musical contest, is one of the most powerful examples. His defeat resulted in an extreme punishment: he was flayed alive. His body was rendered completely vulnerable, offered up to torture, stripped of all status, reduced to exposed flesh.

In classical iconography, Marsyas is not merely naked: he is destitute, defenseless at the mercy of divine power. His nudity is not aesthetic, but political. It embodies the total loss of control.

This emotional register (nudity as a power dynamic) is rarely explored in contemporary photography, because it demands ethical and aesthetic precision: how to show a submissive body without falling into gratuitous cruelty or pornographic imagery?

The answer: through symbolization, not literal reproduction.

The Sacrifice of Isaac

In The Sacrifice of Isaac , Juan de Valdés Leal stages an extreme tension between domination, obedience, and vulnerability—themes that resonate strongly with the myth of Marsyas. The painting captures the suspended moment when Abraham, his arm raised, prepares to strike his son. Isaac, his torso bare and his gaze hidden, is frozen in a mixture of resignation and terror. The offered, exposed body becomes the true focal point: it is here that the symbolic violence of the scene is revealed.

This depiction deeply echoes the logic of Marsyas's torment, where the naked body becomes a territory of absolute domination. Marsyas, bound, stripped, and delivered to a superior power—that of Apollo—embodies total submission to an imposed destiny. In Valdés Leal's work, the same asymmetrical relationship structures the composition: a kneeling, powerless body facing an unshakeable authority poised to exercise its power of life and death.

The artist accentuates this power dynamic through dramatic chiaroscuro. Light strikes Isaac, highlighting the purity of his offered innocence, while Abraham is partially shrouded in shadow, as if the sacrificial act were also removing him from humanity. This dialectic evokes Baroque martyrdom painting, where the radiance of the skin becomes the site of expression for a transcended suffering.

What particularly unites the two works is the way in which nudity is not eroticized, but instrumentalized to reveal a state of total surrender. Isaac is not an ideal or heroic body: he is a submissive, vulnerable body, caught between the earth and the blade, exactly like Marsyas delivered to the vengeful hand of Apollo.

Why is emotion so powerful in nude art?

Exposed nudity under domination tells the story of what the body endures:

loss, humiliation, erosion of power,

but also strength, tenacity, inner resistance.

This type of image explores a rarely used register: the body as a symbolic battlefield, as a place where a struggle takes place between two forces: one that imposes, the other that endures.

And paradoxically, it is often the dominated who becomes the true center of interest, because their body reveals a human depth that the dominant does not have.

The Death of Abel: The Unfulfilled Sacrifice and the Figure of Masculine Vulnerability

In the history of Western art, the figure of sacrifice, particularly that of Isaac, occupies a central place in reflections on violence, lineage, and the vulnerability of the exposed male body. In this respect, Vincent Feugère des Fort's The Death of Abel (1842) at the Musée d'Orsay (or Giovanni Duprem's Abel Mort (1844) at the Hermitage) appears, at first glance, to fall outside this iconographic field. Yet, this sculpture reveals itself to be an inverted mirror of Isaac's story, an essential counterpoint for understanding the tensions between domination, nudity, and the sacrificial gesture.

While the Sacrifice of Isaac depicts violence halted at the very last second, the death of Abel reveals what happens when that violence is unleashed in its entirety. Here, no angel restrains the murderer's hand. Between Abraham and Isaac lies a space of transcendence: a divine hand intervenes and averts death. Between Cain and Abel, on the other hand, there exists only a brutal, opaque human rivalry. Feugère des Forts thus stages the first murder not as a sacred act, but as the most naked manifestation of a violence without justification, without redemption or elevation.

The body of Abel, young, naked, and classically beautiful, becomes the true stage for the drama. Stretched out, offered up, abandoned, it reads like a sacrificed body, even if the cause is no longer divine but fraternal. His limbs slumped, his head thrown back, his throat exposed, everything in his posture evokes the fragility of the subject delivered over to a force beyond his control. Abel resembles Isaac at the moment the blade was about to fall, an Isaac for whom no angel appeared. From this perspective, the sculpture materializes what artists of sacrifice cannot represent: the moment after death. What Rembrandt, Caravaggio, or Titian could not paint because the biblical narrative forbids it, Feugère des Forts exposes with a restrained cruelty: the irreversible consequence of the murderous act.

Abel, in his own way, joins this iconographic constellation: a defenseless being, reduced to the state of pure victim, whose nudity accentuates the sacred and tragic dimension. In the contemporary context of artistic photography, where male nudity often carries the dual weight of desire and danger, The Death of Abel reminds us that the offered body can be a territory of violence as much as of beauty.

The sculpture thus inscribes a profound meditation on vulnerability. Far from any heroism, Abel's body is that of a defeated man, sculpted in the very act of surrender. He does not die for an idea, nor for a god, nor for a higher principle; he dies because humanity carries within itself the potential for destruction. This absence of transcendence makes his body not an offering, but a brutal reminder of our finitude, of what the sacrificial act becomes when nothing restrains it.

And yet, in this fallen body, Feugère des Forts reveals a kind of grace. Abel's surrender, his almost choreographic posture, the purity of the lines, evoke less a corpse than a figure suspended between life and death, between suffering and serenity. This ambiguity nourishes a contemporary interpretation of vulnerability: one in which the male body, often idealized in artistic tradition, here becomes the seat of absolute fragility.

A dialogue

In the dialogue between Isaac, Marsyas and Abel, a symbolic triptych emerges:

Isaac, the body saved

Marsyas, the tortured body

Abel, his body destroyed.

These three figures, brought together in the gaze of the creator or the photographer, trace a complex cartography of male nudity as a space of tension: between offering and exposure, domination and innocence, sensuality and destruction. The Death of Abel occupies a singular place in this geography: that of silence after sacrifice, that of the inexorable.

Undressing for art means offering the creator direct access to the essential: a body that speaks before words, a being stripped of social artifice, a territory where traces of desire, dream, tension and sometimes struggle are inscribed.

Whether it expresses vulnerability, sensuality or domination, nudity remains a powerful language, capable of revealing both the beauty and the tragic depths of human existence.

Conclusion: The exposed body: beauty revealed by the flaw

In the history of art, the exposed body has never been merely a form to be contemplated: it is always the locus of a truth. The naked body, when depicted in its fragility, in the moment when it can be wounded, dominated, offered up, or abandoned, becomes a mirror of our deepest humanity. Whether we observe Isaac immobilized beneath Abraham's knife, Abel stretched out on the ground in the whiteness of the marble, or Marsyas delivered to Apollo's cruelty, what we see is not suffering for its own sake: it is the beauty of the body in the instant when its strength falters.

For the absolute beauty of the human body is never more apparent than when it ceases to be invulnerable. Muscular perfection, ideal anatomy, classical proportions—all this remains superficial as long as the body remains abstract, intact, controlled. True beauty emerges when the body is inscribed within a narrative, a narrative in which it is threatened, disturbed, subjected to the weight of gravity, the vertigo of pain, or the abandonment of movement. It is in the flaw, not in the strength, that humanity becomes visible.

Vulnerability does not diminish beauty: it reveals it. It is even its secret condition.

Abel's body, whether sculpted by Feugère des Forts or Duprè, conveys this with disarming intensity. Stretched out, relaxed, open, it reminds us that nudity is not merely a physical state, but an existential one: that of being seen when nothing protects us. Isaac, in the versions by Caravaggio or Rembrandt, reveals the same truth in a suspended moment: the beauty of the body is not that of the warrior, but that of the innocent who doesn't know if he will live again. As for Marsyas, his utter defeat exposes the human body in its most fragile, yet also most meaningful, aspect.

Thus, in photography as in sculpture, the representation of the exposed body is not intended to magnify power, but to express the mystery of the human condition: a being who seeks to remain upright in a world where everything can overthrow them. The photographer who asks the model to undress is not making a gesture of conquest; they are opening a space where the model can reveal something other than their anatomy: a presence, an intimate vulnerability, a moment when the being shows itself as it truly is.

Absolute beauty is never a superficial radiance.

It is born from the encounter between the perfect form and that which trembles within it. It is the clarity that appears on the edge of disaster, the unstable balance between fall and acceptance.

The exposed body is beautiful because it bears the marks of what threatens it.

And it is precisely in this tension between strength and weakness, between nakedness and dignity, between abandonment and resistance, that the very essence of figurative art is played out.

Human beauty does not reside in the absence of flaws, but in the way light caresses those flaws, giving them a spiritual depth. The vulnerable body, whether sculpted in marble or captured by a lens, reminds us that humanity is never greater than when it accepts its fragility as a form of truth and as a space where beauty is finally revealed.

Further reflection

Religion as a pretext for representing the naked body

For over a thousand years, artists had virtually no other legitimate means of showing a naked, vulnerable, threatened, dominated, suffering, or abandoned body.

Religious narratives were the only accepted stories at the time, because they carried moral justifications.

For example :

Isaac allowed the young body to be shown bound, offered up, exposed.

Abel offered the possibility of the vanquished naked body, stretched out on the ground.

Marsyas (pagan myth) allowed the representation of torture, therefore of extreme tension.

The naked Christ on the cross became the absolute model of the exposed, suffering body.

Saint Sebastian martyr

Without religion, almost none of these images would have been possible.

Thus, when we speak today of Isaac, Abel or Marsyas, we are not speaking of religion, we are speaking of the long history of the body in art.

Religion as a reservoir of archetypes

Religious narratives have produced powerful archetypes. Now, it is precisely these archetypes that interest you as a photographer, because they give a symbolic structure to the vulnerability of the model.

From this perspective, religion is not content, but a narrative framework allowing us to explore the fragility, domination, beauty, abandonment, and emotional truth of the human body.

Religion as a tool to talk about the body, and not about God

In art, religion often provides a means of expression:

of character,

psychology

power dynamics

out of fear,

of desire,

of dignity,

of strength and weakness,

and above all, beauty.

The absolute beauty of the human body shines through precisely in these stories because they give the body a role, a voice, a destiny, an emotional charge. It is not the religious content that matters, but the fact that these stories have allowed us to sculpt, paint, and think about the body for centuries.

The artist is not seeking to illustrate faith, but to explore:

nudity as truth,

Posing as an inner expression

fragility as beauty,

the body as a site of human drama

and presence as a form of grace.

Comments