The son of the fisherman and the mermaid

- Claude Gauthier

- 14 hours ago

- 3 min read

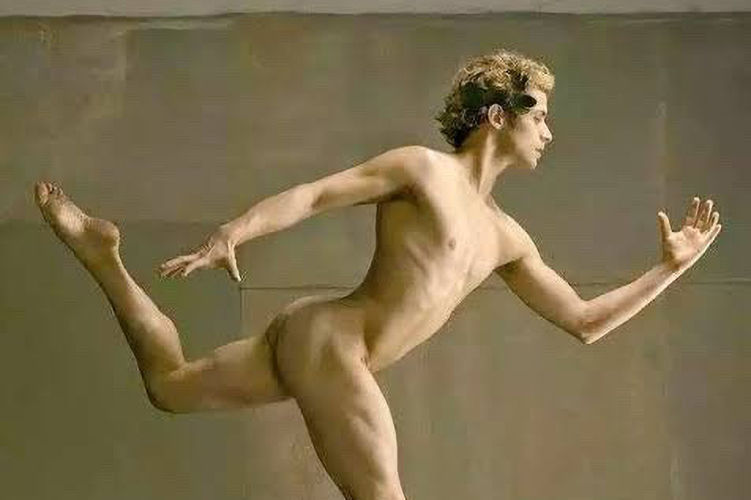

The juxtaposition of Léo Di-Fazio's digital painting *The Fisherman's Son and the Mermaid* with Nano Banana's AI-generated version, artificially aged by forty years, opens up a fascinating territory—pictorial, anthropological, symbolic, and technological. It is not merely a formal exercise; it profoundly questions how art confronts the evolution of the body, the passage of time, and the memory of the image.

Classical art in the face of the evolution of the body

In the history of painting, the young, smooth, harmonious body remains a symbolic ideal. Anatomical perfection evokes heroism, purity, vitality, and even an idea of “universal truth.” In this context, the second image overturns these conventions: it offers not a timeless ideal, but the continuity of a living body, marked by the years, gravity, experiences, and perhaps renunciations.

The body is no longer a sign of the absolute: it tells the story.

A nod to Rambrandt

Rembrandt never sought to flatter his subjects: he showed the truth of the human face, its wrinkles, its weariness, its shadows, its doubts. His self-portraits are not static images but a meditation on time, mortality, and identity , observed through the lens of aging. By painting himself year after year, he created a visual trajectory of time, almost a film before its time, where each image bears witness to an additional existential layer.

Aging an ideal figure: a form of anti-heroism

While classical iconography fixes heroes in an eternal age (Apollo remains forever young, Hercules forever powerful), projecting a character into their future undermines the promise of eternity. This artistic gesture is audacious: it humanizes what has historically been dehumanized into a symbol. It reminds us that beneath ideals lies a real, vulnerable physiology, destined to transform.

We move from mythology to biography.

The use of AI as a narrative extension

AI doesn't simply mimic aging. It becomes a narrative tool, extending the pictorial gesture into the future. AI projects a possible destiny: skin folds, abdominal laxity, postural changes, a melancholic gaze. This isn't a caricature but a plausible physiological interpretation, lending it an almost documentary dimension.

The artist never painted this future, and yet, thanks to AI, we see it.

Aging as a restoration of psychological truth

The young figure stands upright, supple, open, almost innocent. Forty years later, the posture changes: the body closes slightly, the gaze seems heavier, the shoulders slump. Time becomes a sculptural force. The flesh is no longer ideal, but empirical. The body becomes an archive.

This transformation tells not only of biological aging, but also of existential aging: fatigue, wisdom, disillusionment, or simply the gravity of living.

Breaking an iconographic taboo

Very few classical works depict the nude in old age with the same dignity as youthful bodies. The West has glorified youth, ignored maturity, and concealed old age. AI projection breaks this taboo: it shows what would have been censored in academic painting. It is a form of implicit critique of art history.

AI as a speculative tool

This process opens up a new field: it allows us to experiment with visual futures, just as cinema imagines possible worlds. We can age a model, rejuvenate a painting, extend a sculpture, modify a pose, or explore a fictional biography. The artwork becomes dynamic, evolving, multifaceted.

Art is no longer static, but narrative in time.

A reflection on identity

The aging of a painted figure raises a question of identity: are the young model and the old model still the same person? What remains of him? His gaze? His presence? His attitude? Or does time alter even the very essence of a being?

The visual response is unsettling: the young one seems “promise”, the older one “memory”.

A renewal of portraiture practice

Traditionally, a portrait captures a moment in time. Here, the portrait becomes a cycle. It doesn't simply show a body, but its evolution. The work behaves almost like a novel, where each era reveals a layer of meaning.

This process opens up new practices:

evolving portraits

temporal extensions of old paintings

dialogues between youth and maturity

mythologies revisited in bodily reality

Conclusion: an aesthetics of time

Aging an idealized figure is a way of restoring to the image its fragility, its mortality, its human truth. It is not merely a graphic exercise: it is an aesthetic reversal. We move from the absolute ideal to the lived body, from symbol to narrative, from the timeless to the temporal.

AI does not replace the artist; it extends, questions, disturbs, and completes. It reveals what the original painting concealed: destiny, wear and tear, erosion, and continuity.

The work no longer becomes an image, but a life.

Comments