Liberation, The Fall of the Veil

- Claude Gauthier

- 5 days ago

- 6 min read

Libération is a video clip that explores the body as a territory of tension, memory, and transformation. Through a visual dialogue between the sculptures of Auguste Rodin and contemporary images by Lorenzo, using photography, video, drawing, and artificial intelligence, the project questions what society accepts to see, and what it prefers to conceal.

The starting point is historical: the scandal caused by Rodin's nude Balzac at the end of the 19th century, followed by the artist's masterful response with a fully draped figure. These two works are not opposed; they embody two strategies in the face of censorship, two ways of asserting the same truth. The body, when it rejects idealization, becomes subversive.

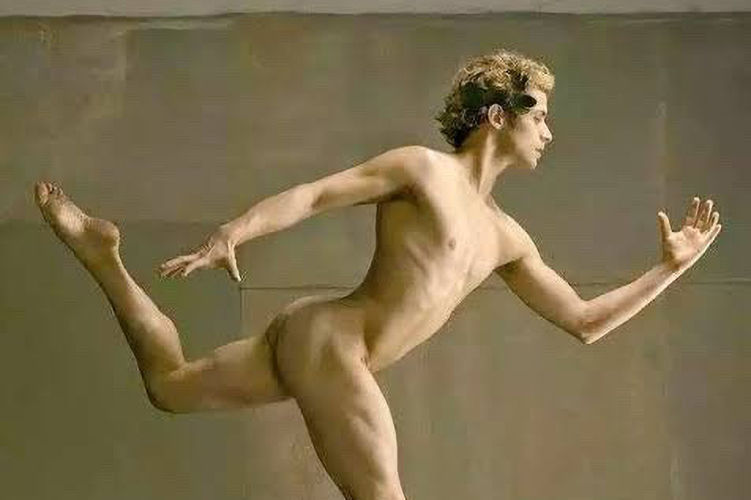

The video translates this tension into the present. Lorenzo initially appears restrained, enveloped, reduced to a barely acceptable presence. Gradually, his body asserts itself, frees itself from the draping, and reveals itself without emphasis or provocation. This unveiling is neither spectacular nor militant: it is an act of precision. The gesture matters more than the final image.

The trajectory does not end with the exposure of the body, but with its erasure. The filmed body becomes a drawing, the drawing becomes a trace. Libération thus offers a journey: from scandal to acceptance, from matter to memory, from the seen body to the felt body. It is not a celebration of nudity, but a reflection on what it still means today to fully inhabit one's body.

Historical perspective

Balzac: From the scandalous body to the draped body

When Auguste Rodin began work on the monument to Honoré de Balzac in 1891 at the request of the Société des Gens de Lettres (Society of Men of Letters), he embarked on a project that went far beyond a simple commemorative commission. Balzac was then a revered, almost untouchable, tutelary figure. Rodin was expected to create a statue worthy of the literary myth: noble, recognizable, and flattering. But Rodin rejected this approach from the outset. He did not seek to represent the social man, but rather to embody the creative force.

Rodin began by studying Balzac's body in a way that defied academic ideals. He inquired about his late-life corpulence, his excesses, and his visceral relationship with writing. He produced numerous drawings and studies of nudes, not to shock, but to understand how a real body could embody inner power. The first nude Balzac is neither heroic nor seductive: heavy forms, a prominent belly, a massive posture. Rodin depicts a body shaped by energy, almost deformed, traversed by a creative tension. This Balzac is not idealized; he is inhabited.

It is precisely this approach that provokes the scandal. At the end of the 19th century, sculptural nudity was acceptable when it conformed to classical canons: youthful bodies, ideal proportions, normative beauty. Balzac's nude, old, massive, and uncompromising, is perceived as an offense. Even more so, it attacks a fundamental taboo: that of representing a great man in his physical truth, and not in a socially acceptable image. The public sees not an embodiment of genius, but a degradation of the icon.

Faced with the fierce rejection of critics and patrons, Rodin did not give up. He understood, however, that the problem was not the body itself, but the way it was perceived. A few years later, he returned to Balzac with a radically different approach: he completely enveloped the body in a heavy dressing gown. From this draped mass, only the face emerged. The body disappeared, but paradoxically, the presence became even more overwhelming.

This second Balzac is not a capitulation. It is a masterful act of defiance. By covering the body, Rodin does not submit to academic expectations; he subverts them. The sculpture still does not flatter: it rejects anatomical detail, faithful portraiture, historical narrative. The form becomes a block, almost a monolith. The genius is no longer in the body shown, but in the overall form, in the verticality, in the suggested inner mass.

Rodin understood that drapery acts as an acceptable social mask. He gives the public what it demands—decency—while preserving the essential: the monumentality of the spirit. Where the nude exposed the truth of the body too directly, drapery imposes silence, distance, and transforms sculpture into a symbol. The scandalous body becomes invisible, but it is not denied: it is absorbed into the form.

Thus, between the nude Balzac and the draped Balzac, Rodin does not change his vision. He refines his strategy. He moves from frontal confrontation to a sovereign irony, demonstrating that genius does not need to be beautiful to be true, nor visible to be powerful.

Symbolic perspective

From the constrained body to the sovereign body

The Liberation project is part of a symbolic dialogue between the work of Auguste Rodin and Lorenzo's contemporary images, using photographs, drawings, and video to question the place of the body in the social gaze. Through a succession of visual transformations, the body becomes the site of a passage: from idea to matter, from censorship to affirmation, and then from presence to trace.

In Rodin's work, the nude Balzac appears as a brutal revelation. Far from the academic ideal, the massive, imperfect body embodies an inner energy, a creative force inseparable from the flesh. This choice provokes scandal: the public refuses to see genius in a non-conforming body. Rodin's response, a few years later, is just as radical. By enveloping Balzac in thick drapery, he does not abandon his vision; he shifts it. The body disappears, but the power remains, concentrated in the mass and verticality of the form.

Libération transposes this historical tension into the present. Lorenzo initially appears as a restrained figure, concealed beneath a red cape, reminiscent of Rodin's drapery. Photography and video show a body held back, tolerated as long as it remains abstract. The act of removing the cape then becomes an act of rupture: the body exposes itself, not to seduce, but to exist fully. The direct gaze affirms a presence without justification.

The project, however, does not end with a statement. The body gradually transforms into a drawing, then disappears. This final disappearance is not a negation, but a sublimation. After having been matter, a mask, and a struggle, the body becomes a trace, a memory, and a shared experience. Liberation does not celebrate nudity; it reveals the path by which the body, confronted with the gaze, rediscovers its inner sovereignty.

Script for a 60-second music video

General intention

From scandal to concealment, then from concealment to liberation, until erasure: the body becomes trace, memory, breath.

Guiding thread: The body goes through four states: idea → matter → constraint → liberation → trace . Each transformation is not aesthetic, but existential and symbolic.

1. Drawing of Balzac naked, seated

Symbolism: The body in its abstract, unformed state. The drawing represents the initial, raw thought , before any censorship. Seated, the body is still internal , contained, fragile. It is not yet exposed to the social gaze. It is not yet recognizable.

2. Drawing of Balzac naked, rising

Symbolism: The transition to verticality marks the awakening ofawareness . Standing up means accepting to be seen, assuming one's presence in the world.

3. Superimposition of the drawing and sculpture of the nude Balzac (1892)

Symbolism: Thought becomes matter. The idealized body confronts the reality of the public gaze. This is the moment of scandal : the naked truth is disturbing.

4. Transformation towards the wrapped Balzac (1897)

Symbolism: The cape embodies the social reaction : to conceal in order to appease, to cover in order to make acceptable. The body is still there, but neutralized , rendered abstract.

5. The wrapped sculpture becomes Lorenzo

Symbolism: The historical myth slips towards the contemporary individual. Lorenzo inherits the symbolic weight of Balzac: shame, protection, the norm are transmitted.

6. Lorenzo visible only from the head

Symbolism: Intellectual identity is tolerated, the body is not. Society accepts the face, but rejects the expression of the body .

7. Lorenzo opens his arms, the wind lifts the cape

Symbolism: The body resists. Lorenzo, bare-chested, arms outstretched, appears in control of his movements. The wind symbolizes inner strength , the desire for emancipation. The cape flutters: the constraint is no longer absolute.

8. Abrupt gesture: Lorenzo takes off his cape

Symbolism: An act of rupture. Liberation is not gentle: it is voluntary, risky, irreversible . The cape flies away like a rejected norm.

9. Lorenzo, shirtless, arms outstretched horizontally

Symbolism: The body is fully embraced. The open arms evoke both crucifixion , offering, and vulnerability. The direct gaze into the camera affirms: "I am here."

10. Lorenzo lowers his head, closes his eyes and lowers his arms

Symbolism: The struggle ends. This gesture marks reconciliation : the body no longer needs to convince. It is accepted, not as a demand, but as an intimate presence.

11. Lorenzo's body transforms into a drawing that simplifies and disappears

Symbolism: The flesh returns to the idea. After the exposure comes the voluntary erasure. The body disappears, but the trace remains in the memory of the viewer . It is not a disappearance, but a transmission .

Conclusion

The body is neither scandal, nor object, nor struggle. It is a passage.

This scenario does not show a body that imposes itself, but a body that traverses history, gaze and silence .

Comments